For most of my life, I thought about morality in terms of categories—some people are good, some are bad, and most fall somewhere in between. But a recent shift in thinking made me reconsider this framing altogether. What if goodness isn’t a fixed essence, but context-bound and role-specific? What if a person can be good to some, indifferent to others, and bad to the rest—not at random, but in consistent ways within each group?

That may sound trivial—of course people behave differently with different people. But if that observation hasn’t transformed how we think about judgment, character, or ethics, then maybe it’s not so trivial. Maybe we’ve known it, but not really felt it. Not traced its consequences. Not let it disrupt the comforting illusion that someone can simply be “a good person.”

Take, for example, a married gay man living a closeted life. He might deceive his wife, hurting her deeply, while at the same time being generous, kind, and affirming in the gay community. Is he good or bad? That question becomes less meaningful when you realize he may be morally congruent within each subset of his life—he simply has different ethical modes that operate based on perceived relationships.

This isn’t moral relativism in the cultural or ideological sense. It’s a reframing of intra-personal moral structure. A single individual can have localized consistency—being good within one relational context, harmful in another, and yet behaving according to a stable internal logic in each. Their actions aren’t random or hypocritical—they’re modular.

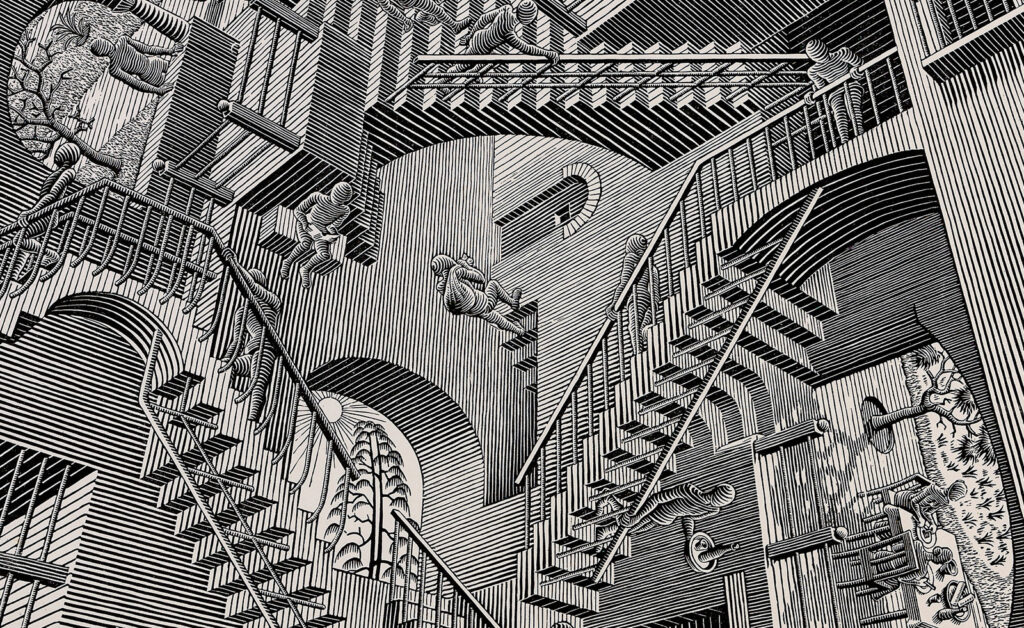

Escher’s Relativity captures something similar in visual form: figures move confidently through a world that seems coherent from within each stairway system, yet impossible when viewed as a whole. Each path makes sense locally—but globally, they can’t all be true at once.

This modular view of morality directly contradicts classical models like Plato’s. In The Republic, Socrates insists that justice within a person means inner harmony—reason governing spirit and appetite. Someone who behaves inconsistently across domains, no matter how discreetly, is corrupting their soul. But the modular lens challenges that assumption. A person might be fragmented in their moral behaviour, yet entirely consistent within each of those fragments.

Others offer frameworks that better accommodate this view. Nietzsche, for instance, dismisses universal morality as a fiction—constructed by the powerless to restrain the strong. Values, for him, are tools of interpretation. A person who’s cruel in one setting and kind in another isn’t confused; they’re simply responding to different dynamics of power. In this light, modular morality isn’t incoherence—it’s honesty.

Buddhism, too, recognizes the absence of a fixed self. Behaviour arises not from character, but from conditions—intention, attachment, ignorance. A person’s different moral expressions across contexts don’t signal contradiction, but simply the karmic traces of different relational fields. What matters is not consistency, but whether one is deepening patterns of greed, hatred, and delusion—or loosening them.

By contrast, Aristotle might challenge the modular model. His virtue ethics emphasizes the cultivation of stable moral character over time. While he acknowledges that context matters, he believes the good person gradually integrates their values across all roles. Modular morality, from that view, may be descriptively accurate—but ethically immature.

Modern psychology, unlike ancient philosophy, seems to fully endorse the modular view without moral panic. Concepts like cognitive dissonance, moral licensing, compartmentalization, and relational schemas all describe people whose ethical behaviour changes based on context—not because they’re dishonest, but because the human mind is contextual. Within each context, many of us are entirely consistent.

So perhaps we’re not morally chaotic—we’re morally partitioned. Not incoherent—just selectively coherent.

The takeaway isn’t that we should accept harm or excuse betrayal. Rather, it’s to recognize the limits of moral labels. Instead of asking “Is this person good or bad?”, we can ask:

“To whom? In what role? According to what internal frame?”

This opens the door not to moral relativism in the dismissive sense, but to moral specificity. It gives us tools to describe what’s actually happening without flattening it into judgment.

And maybe that’s the beginning of a more honest, usable ethics—not about being “good,” but about being aware of who we are good to, and whether that’s enough.