They say they believe in democracy — but only when it serves them. The modern conservative movement, especially in North America, increasingly behaves like a bad-faith player: eager to contest elections, but unwilling to accept outcomes that contradict their will. This pattern, visible from Trump’s resurrectionists to Alberta’s recurring separatist murmurs, is more than sour grapes. It reveals a conditional loyalty to democratic principles — a form of participation that verges on sabotage.

This isn’t just about losing. Everyone hates losing. But most people, most parties, lick their wounds, regroup, and try again. What we’re seeing instead is something deeper: a refusal to even acknowledge the loss as legitimate. That’s not political disappointment. That’s something closer to cheating.

When Trump lost in 2020, he declared victory anyway. Millions believed him. They stormed the Capitol in costumes and camo, waving flags for a man rather than a country. Five years later in Canada, the Conservatives earned more votes than ever — 41% — but still lost. The Liberals edged them with 43.7%, yet that narrow margin gave them 169 seats to the Conservatives’ 147. A small lead turned into a big advantage — the usual magic trick of first-past-the-post.1 To make matters worse, the Conservative leader lost his own seat. Until someone offers him theirs, he can’t even stand up in Parliament to shout about how unfair it all is. And instead of reflection, came rejection. Danielle Smith, Alberta’s conservative premier, floated yet again that maybe Alberta would be better off on its own2 — not because the vote was fraudulent, but because it didn’t flatter them.

This isn’t always loud. Sometimes it takes the form of quiet secessionism — not literal departure, but emotional withdrawal from a shared civic reality. Alberta’s recurring “Western alienation” narrative leans on this idea: that Canada isn’t really one country, but two irreconcilable visions trapped in a room they can’t leave. It’s not just disappointment. It’s a kind of ideological divorce.

Why does this happen? Why this pattern of rejection, deflection, and retreat?

Part of the answer lies in psychology. Some people fuse so deeply with their political identity that disagreement feels like betrayal. For them, the party isn’t a vehicle for policy. It is the self. Studies in identity fusion theory show that when people experience their group as an extension of themselves, they can become willing to defend it at all costs — even when that defense turns destructive.3

But this kind of cognitive rigidity doesn’t arise in a vacuum. It’s nurtured by tightly sealed social environments that reward belief over evidence. Where once Fox News served as the home base for this worldview — created after Watergate as a deliberate counter to what conservatives saw as media bias — now a fragmented ecosystem has taken over. Fringe influencers, Substack prophets, and video streamers each stake their authority not on verifiable knowledge, but on emotional allegiance. Their entire currency is the rejection of consensus. Their power lies in breaking trust, not earning it.

And the effect is strong. One study found that people’s social settings often shape their political reactions more than their own partisan leanings do.4 In communities where rejecting election outcomes is normalized, disbelief becomes a signal of loyalty. Truth is no longer something you discover. It’s something you declare.

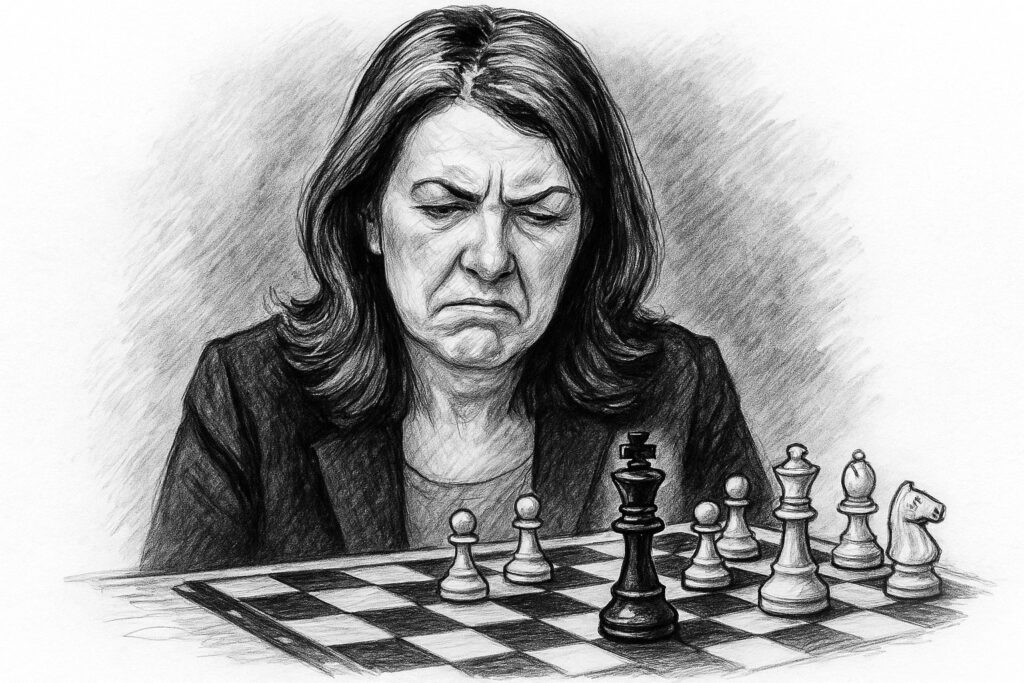

There’s a reason this behavior feels dishonest. Because it is dishonest. It’s like watching someone sit down to play chess, make bold claims about their genius, and then — just as checkmate begins to materialize — they casually swipe the board to the floor, scatter the pieces under the table, and announce they never really cared for chess anyway. Not because they lost, but because losing was never supposed to be on the table. The game was only valid if they won it.

This isn’t principled opposition or even ideological extremism. It’s a deeper kind of bad faith: the kind that participates in democracy without believing in it. The kind that pretends to play fair while quietly pocketing the dice. And that’s not just dysfunction. That’s the beginning of democratic decay. A hollowing-out from within. A system that still speaks the language of democracy, but no longer trusts the voice on the other end.

Footnotes

1. First-past-the-post strikes again. In 2025, the Liberals received 43.7% of the popular vote and won 169 seats; the Conservatives, with 41%, won just 147. The system rewards vote distribution, not total support. And despite past promises to reform it, both major parties have quietly kept the system — especially once it starts working in their favour.

2. After the 2025 election, Smith proposed making it easier for citizens to trigger referendums — a move widely seen as stoking separatist sentiment. She denied pushing for separation, but First Nations leaders publicly called on her to stop “stoking separatism.” CTV News

3. Swann, W. B., Jr., Jetten, J., Gómez, Á., Whitehouse, H., & Bastian, B. (2012). When group membership gets personal: A theory of identity fusion. Psychological Review, 119(3), 441–456. Read here. This study explains how identity fusion — the deep merging of personal and group identity — can lead people to act in extreme or even anti-social ways in defense of their group.

4. Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2016). Independent politics: How American disdain for parties leads to political inaction. Cambridge University Press. Read excerpt. This work shows that political preferences are often shaped less by ideology and more by the social environments people inhabit — especially when those environments discourage dissent and reward conformity.